What does knowledge exchange look like for a historian?

As a historian at the Open University I am interested in how national identities are shaped by ideas about history. For hundreds of years, much of how people have conceptualised the four nations of the UK has hinged on their assumptions about the past. Originally my research focused on the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. More recently, however, I have become interested in how imaginings of the past help to shape national identities today.

Investigating people’s attitudes and outlooks in the present day is a very different proposition from the historian’s usual territory of perusing the legacies and leftovers of long-dead generations. That’s particularly the case if you want to find out, as I do, how people in marginalised communities think about their sense of nation and the history that informs it. Public narratives about the past tend to be shaped by those with power; whether it be cultural, social, political or economic. As such they reflect the worldviews of elites. What I’m interested in is voices that are seldom heard, and the history and heritage that matters to them.

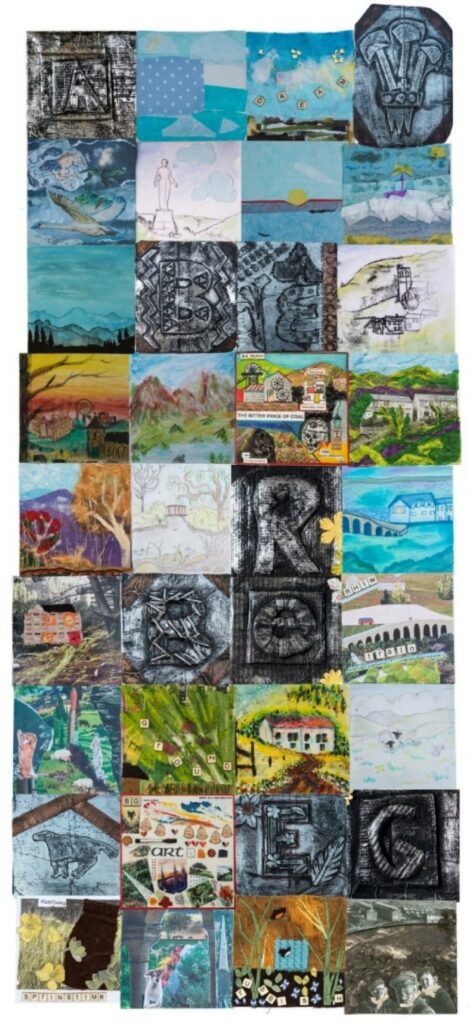

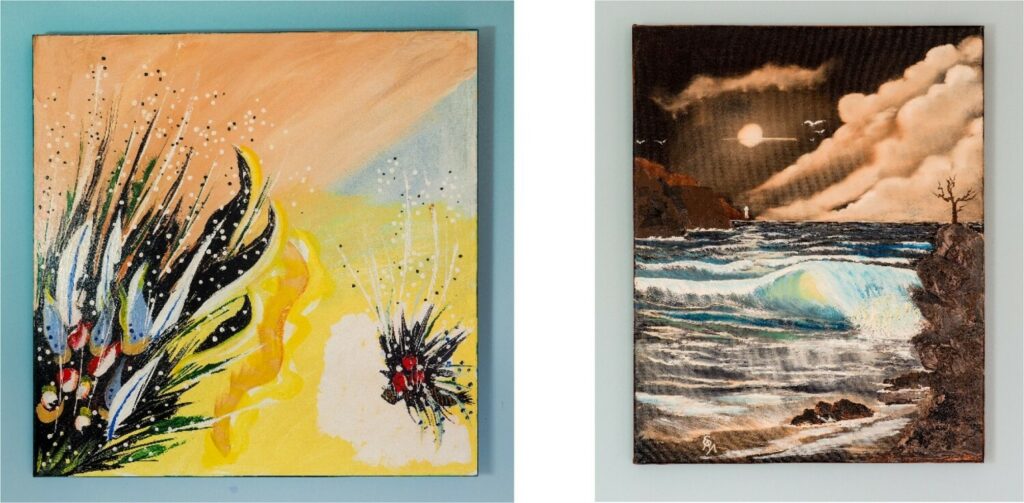

To that end, my colleagues and I secured funding from UKRI at the start of 2020 for BG REACH (Blaenau Gwent Residents Engaging in Arts, Culture and Heritage). This was an exploration of local heritage in an economically declining post-industrial area of the South Wales Valleys. The project supported participants to use arts-based approaches such as creative writing, musical composition and visual arts to produce creative reflections on aspects of heritage that they associated with the region. These were delivered through public workshops in which attendees were taught various creative and heritage-related skills, and then supported to use them to produce outputs. Heritage was the subject of the project, but the use of creative arts approaches resulted in a rich array of material that could be analysed as cultural products, and also helped to get people through the door. Despite the COVID 19 pandemic, by autumn 2021 BG REACH had worked with 43 residents who had between them produced 66 creative reflections on the history of Blaenau Gwent.

Those results were achieved by a three-way partnership built upon meaningful knowledge exchange. The Open University provided knowledge of history and heritage, and experience in delivering programmes of community-based learning. Linc Cymru housing association offered strong connections with the local community and expertise in how to garner engagement. And Aberbeeg Community Group, the project’s third partner, championed project activities on the ground and used the respect and standing of its members to mobilise interest. By working together, each organisation developed its grasp of the whole. Moreover, the process of working directly with community members also helped all three partners to develop a more informed and holistic sense of how to do this kind of work effectively.

BG REACH was a research project. It found that, contrary to expectation in an area where ways of life had until recently been shaped by coal and steel, industrial heritage was not the main theme of interest for people living there. Instead, the art music and writing they made showed a preoccupation with the region’s deeper past as well as the contemporary revitalisation of the area’s natural heritage as a consequence of deindustrialisation. In addition, although only a minority of participants spoke Welsh, many of their outputs drew on motifs of Welshness. This belies a scholarly consensus that, without a strong language base to sustain it, Welsh identity in the south of the country is in terminal decline. Ultimately, the work produced suggested that local identities in the South Wales coalfield may not be as defined by the industrial experience as is usually assumed.

But BG REACH was also a community development project. As their testimony reveals, it contributed to the wellbeing of participants by equipping them with new skills, fostering new relationships, and connecting them with a sense of the past. In so doing, it addressed the goals relating to community cohesion and vibrant culture laid down in the Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act (2015). What’s more, the project did more than solicit and record creative reflections on heritage from a socio-economically deprived and culturally stigmatised community. It also amplified them. A three-month exhibition of project outputs, co-designed with participants, was staged at St Fagans National History Museum on the outskirts of Cardiff. It attracted over 18,000 visitors, acting as a rebuttal to elite-led narratives of Wales’s past and a riposte to place-based stigma through the talents of the people who live there.

Following the success of BG REACH, the National Lottery Heritage Fund have provided financial support for the scoping phase of a follow-on project called Wales REACH. This bigger and bolder REACH will run for two years, offering a far greater range of heritage and creative arts activities than its predecessor. It will work with five communities across Wales that are disadvantaged by dint of socio-economic status, ethnicity, age, location and / or disability. For Wales REACH, heritage and creativity will offer a means of bringing disparate communities together and adding a new dimension to the knowledge exchange already underway.

The project’s other goals, however, will be the same, using heritage and the creative arts as a means of equipping participants with new skills, contributing to community cohesion, boosting peripheralized voices, and learning more about how intersections between heritage and identity in different versions of Welshness. So too will its delivery model; working with housing associations as a route into participating communities; working with community groups as a means of fostering trust and making connections on the ground.

The point about these projects is that (a) they are designed to do multiple things at the same time, and (b) their ethos is one of collaboration with communities. In this way they act as a reproach to traditional notions of ‘impact’, in which research is conducted in the academy and then taken out into the world to be shared. The crux is to do research with communities and non-academic partners, and to design that research in ways that have multiple simultaneous benefits for multiple collaborating stakeholders. This is a ‘do with’ rather than a ‘do to’ approach, and it can oftentimes yield much better outcomes for all concerned.

Dr Richard Marsden

Senior Lecturer and Academic Lead for the Open College of the Arts

The Open University